Year:

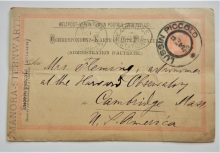

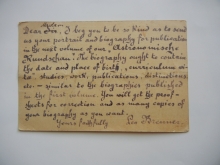

This postal card represents an historic and unique communication between two of the world’s foremost astronomers – Leo Brenner and Williamina Fleming. See biographical information below. The Austria postal card has an 1899 postmark from Lussin Piccolo, a Croatian Island in the northern Adriatic Sea…rare in its own right. At left is a handstamp for Manora-Sternwarte, the observatory founded by Leo Brenner. The card is addressed to Mrs. Fleming at Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. Brenner, whose signature is at the bottom of the card, miswrote his salutation as Dear Sir (probably because few, if any, women had reached such stature in the field of astronomy at the time). He corrected the error before posting his request that she send an image of herself along with a biography for use in his astronomy publication. Card has a light horizontal crease. Otherwise, very clean. Cambridge receiver postmark on address side.

Spiridon Gopcevic or Gopcevia was a Serbian astronomer and historian. He is also known by his pen name of Leo Brenner. He was born to a shipowner in the Austrian litoral town of Trieste (today in Italy), and at an early age, was sent to Vienna to be educated. Following the death of his mother, he became a journalist by trade. Among his works he published Macedonia and Old Serbia in 1889, an ethnographic study. However, he spent time in jail in 1893 due to some of his articles against the Austro-Hungarian government, and decided to end his journalistic career. In 1893 he founded Manora Observatory on Mali Lošinj. This observatory was named for his wife, a wealthy Austrian noblewoman. At this observatory, Spiridon used the 17.5cm refractor telescope at the observatory to make observations of Mars, the rings of Saturn, and other planets. He would eventually close the observatory in 1909 due to financial problems. From 1899 until 1908 he was the founder and editor of the Astronomische Rundschau, a popular scientific journal. He spent several years in America before returning to Europe and editing an army journal in Berlin during the war. The crater Brenner on the Moon was named after him (based on his nom de plume) by his friend Phillip Fauth. A new observatory was built on Mali Lošinj in 1993, and was named "Leo Brenner".

Williamina Paton Stevens Fleming (15 May 1857 – 21 May 1911) was a Scottish astronomer active in the United States. During her career, she helped develop a common designation system for stars and cataloged thousands of stars and other astronomical phenomena. Among several career achievements that advanced astronomy, Fleming is noted for her discovery of the Horsehead Nebula in 1888. Williamina Paton Stevens was born in Dundee, Scotland on 15 May 1857. In 1877, she married James Orr Fleming, an accountant and widower, also of Dundee. She worked as a teacher a short time before the couple emigrated to Boston, Massachusetts, when she was 21. The couple had one son, Edward P. Fleming.

After she and her young son were abandoned by her husband, Williamina Fleming worked as a maid in the home of Professor Edward Charles Pickering, who was director of the Harvard College Observatory. Pickering's wife Elizabeth recommended Williamina as having talents beyond custodial and maternal arts, and in 1879 Pickering hired Fleming to conduct part-time administrative work at the observatory.[4] In 1881, Pickering invited Fleming to formally join the HCO and taught her how to analyze stellar spectra. She became one of the founding members of the Harvard Computers, an all-women cadre of human computers hired by Pickering to compute mathematical classifications and edit the observatory's publications.

During her career, Fleming discovered a total of 59 gaseous nebulae, over 310 variable stars, and 10 novae.

Most notably, in 1888, Fleming discovered the Horsehead Nebula on a telescope-photogrammetry plate made by astronomer W. H. Pickering, brother of E.C. Pickering. She described the bright nebula (later known as IC 434) as having "a semicircular indentation 5 minutes in diameter 30 minutes south of Zeta Orionis". Subsequent professional publications neglected to give credit to Fleming for the discovery. The first Dreyer Index Catalogue omitted Fleming's name from the list of contributors having then discovered sky objects at Harvard, attributing the entire work merely to "Pickering". However, by the time the second Dreyer Index Catalogue was published in 1908, Fleming and her female colleagues at the HCO were sufficiently well-known and received proper credit for their discoveries.

Fleming is also credited with the discovery of the first white dwarf:

The first person who knew of the existence of white dwarfs was Mrs. Fleming; the next two, an hour or two later, Professor E. C. Pickering and I. With characteristic generosity, Pickering had volunteered to have the spectra of the stars which I had observed for parallax looked up on the Harvard plates. All those of faint absolute magnitude turned out to be of class G or later. Moved with curiosity I asked him about the companion of 40 Eridani. Characteristically, again, he telephoned to Mrs. Fleming who reported within an hour or so, that it was of Class A.

— Henry Norris Russell

Fleming published her discovery of white dwarf stars in 1910.[3] Her other notable publications include A Photographic Study of Variable Stars (1907), a list of 222 variable stars she had discovered; and Spectra and Photographic Magnitudes of Stars in Standard Regions (1911).

She died of pneumonia in Boston on 21 May 1911.

Fleming openly advocated for other women in the sciences in her talk "A Field for Woman's Work in Astronomy" at the 1893 World's Fair in Chicago, where she openly promoted the hiring of female assistants in astronomy. Her speech suggested she agreed with the prevailing idea that women were inferior, but felt that, if given greater opportunities, they would be able to become equals; in other words, the sex differences in this regard were more culturally constructed than biologically grounded.

In 1906, she was made an honorary member of the Royal Astronomical Society of London, the first Scottish woman to be so honored.[3] Soon after she was appointed honorary fellow in astronomy of Wellesley College. Shortly before her death the Astronomical Society of Mexico awarded her the Guadalupe Almendaro medal for her discovery of new stars.