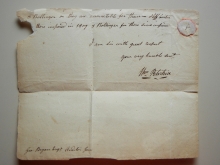

The signature of William Petrikin should rank up there with signatures on the Declaration of Independence. See details below of his contribution to the fundamental principles of the United States. This letter fragment has great historic significance.

William Petrikin, born in Scotland. Moved to Carlisle PA and then Bellefonte, PA Died 9/20/1821. Author of “The Scourge” January 23, 1788. He was an anti-Federalist leader and a major writer involved with the birth of the US Government Bill of Rights.

From an historic source: The onset of the town of Bellefonte began in 1797 (not in 1795 as stated by the current town government) since the offer to purchase the land had questions as to who owned the land and it was 1797 before the deed was quieted. Still a very influential Federalist politician and wealthy merchant from Carlisle decided in 1795 to sell his business and move to Bellefonte. Why did William Petrikin give up great wealth to come here? Research his stint as a Federalist who was one of 22 Federalist from the Carlisle area who fought against part of the Constitution they felt would allow our government to become government by the government. The boiling point of their anger occurred when the other Federalist decided to have a victory party in the hotbed of the opposition, Carlisle, and the people rioted. Petrikin and 21 of his friends were put in jail for inciting a riot. After a day or two they were released for the government realized this was government by the government. The area from Carlisle to Chambersburg was loaded with people of their view thereby they fled to the wilderness to escape the control of the government. These people also knew that the purest iron in the world was to be found there and since it was the iron age, iron was the kingmaker of the world. Add to this the fact that limestone was also needed to make iron and the limestone is still being mined in large quantities here over two hundred years later. Add to this that another need for iron making was fuel to fire the furnaces and the entire area was covered by hardwoods and later millions of tons of coal were mined in the area.

From a second source: No group in American political history was more heterogeneous than Antifederalism. Even a cursory glance of the final vote on ratification demonstrates the incredible regional and geographical diversity of the Antifederalist coalition. Antifederalism was strong in northern and western New England, Rhode Island, the Hudson River Valley of New York, western Pennsylvania, the south side of Virginia, North Carolina and upcountry South Carolina. The opposition to the Constitution brought together rich planters in the South, “middle class” politicians in New York and Pennsylvania, and backcountry farmers from several different regions. Among leading Antifederalist voices one could count members of the nation’s political elite -- aristocratic planters such as Virginia’s George Mason and the wealthy New England merchant Elbridge Gerry. Mason and Gerry were adherents of a traditional variant of republicanism, one which viewed the centralization of power as a dangerous step toward tyranny. The opposition to the Constitution in the mid-Atlantic, by contrast, included figures such as weaver-turned-politician William Findley and a former cobbler from Albany, Abraham Yates. These new politicians, drawn from more humble, middling ranks, were buoyed up by the rising tide of democratic sentiments unleashed by the American Revolution. These men feared that the Constitution threatened the democratic achievements of the Revolution, which could only survive if the individual states – the governments closest to the people -- retained the bulk of power in the American system. Finally, Antifederalism also attracted adherents of a more radical plebeian view of democracy. For these plebeian populists, only the direct voice of the people as represented by the local jury, local militia, or the actions of the crowd taking to the streets, could fulfill their radical localist ideal of democracy. The democratic ethos championed by Findley and Yates proved far too tame for plebeian populists, such as William Petrikin, the fiery backcountry radical from Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

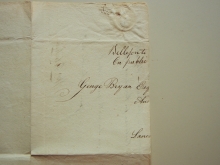

The letter is addressed to George Byron who was the Harrisburg Pennsylvania auditor general involved with Revolutionary War pensions.