Year:

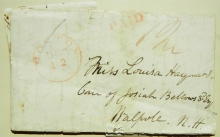

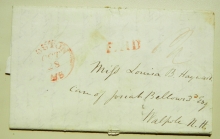

Two interesting letters from Charles Hayward of Boston to his cousin Louisa in Walpole New Hampshire. In the first letter, Charles, who has just returned from a visit to Walpole, comments on how much Louisa has grown and that he, being older and wiser, will now impart some important life information to him. Some comes in an October 27, 1837 letter and more in a December 5, 1837 letter.

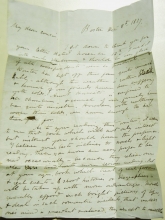

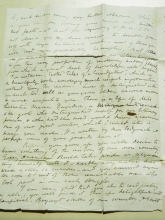

In the first letter, he describes his journey home with Aunt Harriet…”we suffered extremely with the cold, but should be willing to suffer a good deal more for the sake of so pleasant a visit as we had at Walpole.” Regarding Louisa he writes: “On many accounts you are particularly well situated for the formation of your character and cultivation of your mind. A person in the country is thrown on his own resources, he has fewer interruptions, fewer exciting pleasures and more time for reflection than if dwelling in town.” After some elaboration, he continues: “Then you are an only daughter & therefore will necessary be your mother’s chief companion ere she looks to you for assistance, presently she will rely on your judgment & gradually transfer her cares to you – I doubt not that you would gladly receive them.” The discourse continues and he suddenly breaks the train of thought with “we have just heard the news of a great piracy off the mouth of the Delaware River. The report is that a London & Philadelphia packet with about 60 passengers & large sums of money have been captured and carried to sea. Today’s mail has brought no news concerning it and possibly it may not be the case.” (for more on this event, go to http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=2293&dat=19440709&id=NBUnAAAAIBAJ&sjid=sAIGAAAAIBAJ&pg=1287,1613441). There is more to the letter. It is in reasonable condition with a fairly large hole where the seal was torn.

The second letter is more specific in advice to Louisa on her upbringing. He mentions that Louisa likes novels and light reading. He recommends short histories and biographies as offering “more advantages”. “For instance, Scott’s ‘Tales of a Grandfather’ which is a beautiful book conveying much useful information without tiring the reader…there is a life of Miss Lucretia Maria Davidson, a remarkable girl, who distinguished herself for her literary prowess & who, had she lived, would have become one of our first writers, which I should like to have you read. It is written by Miss Sedgwick & perhaps some of your friends have it.” (See below). He recommends books on American history and old world poets such as Burns, Shakespeare and Milton. “If I were you, I would not read Byron. He was a bad man and although many of his poems are beautiful, many more are immoral and some blasphemous.” He concludes by recommending religious reading; specifically the bible. There is more to the letter, principally of a family nature. This letter has separations and a hole where the seal was broken. It is easy to read.

The Boston Directory of 1861 lists four Charles Haywards. Was unable to further pinpoint the writer.

There are a number of matching names in Massachusetts Historical Society records. Lemuel Hayward (d. 1821) was married first to Sarah Savage, then to Sarah "Sally" Henshaw (1768-1849). With Sally, he the following children: Charles Hayward (1787-1855), who married Ellen Dorr; George Hayward (1791-1863), whose second wife was Mary Ann Binney, previously married to Amos Binney; Joseph Henshaw Hayward (1789-1853); Sarah A. Hayward (b. 1794), who married Samuel Adams Dorr; Joshua Henshaw Hayward (1797-1856); and Harriet Stillman Hayward (1803-1883), who married Thomas W. Wyman.

Joseph H. Hayward was married to Mary May Davenport (1795-1843), and their children included Mary Davenport Hayward (1818-1886), who married George A. Whitney; Louisa Davenport Hayward (1826-1876), who married George H. Frothingham; Isaac Davenport Hayward (1828-1878); Harriet Stillman Hayward (b. 1830), who married William C. Winslow; Catherine Davenport Hayward (1833-1923), who married Samuel H. Savage; and Josephine Hayward (1836-1917), who married Henry P. Binney.

Walpole records show there is a Louisa B. Woodward house which is a local point of interest.

Lucretia Maria Davidson (September 27, 1808 – August 27, 1825) was an American poet of the early 19th century. She was born in Plattsburgh, New York, on September 27, 1808. Her father, Oliver Davidson, was a physician, and her mother, Margaret Miller, was an author. She was sent at the age of four to Plattsburg Academy, where she learned to read, and wrote Roman letters in the sand. Lucretia learned to write in her seventh year, and developed a great fondness for reading. Before she was twelve she had read much history, and the dramatic works of William Shakespeare, Oliver Goldsmith, and August von Kotzebue, with many popular novels and romances. Davidson was an extremely precocious child, and she wrote the earliest specimen of her verse, “Epitaph on a Robin,” at the age of nine. She wrote poetry rapidly, when in the mood, but preferred to be alone while composing, often burning an unfinished piece that had been seen by others. She was fond of childish sports, but would often stop in the midst of them to write, when struck with an idea for a poem.

When about fourteen years old she was allowed to attend a ball in Plattsburg, but, in the midst of her preparations, was found sitting in a corner writing verses on “What the World Calls Pleasure.” In October 1824, a gentleman visiting Plattsburg saw some of her verses, and offered to give her a better education than her parents could afford. She was accordingly sent to Mrs. Willard's school in Troy, N. Y., but her studies undermined her health, and she returned home. After her recovery she was sent to Miss Gilbert's school in Albany, but remained there only about three months before she was taken home to die. Davidson died at Plattsburgh on August 27, 1825, at the age of 16 years and 11 months of tuberculosis. Davidson wrote prolifically in her short life, and her surviving poems, of various lengths, number 278, among these being five pieces of several cantos each.

Davidson was praised, with varying levels of enthusiasm, by such notable figures as Edgar Allan Poe, Robert Southey, Marceline Desbordes-Valmore and Catharine Maria Sedgwick. Sedgwick wrote a biographical sketch which was included with Davidson's Poetical Remains, and Desbordes-Valmore wrote an ode to her.

Southey's influential, romanticizing 1829 study of her, which compared Davidson to Thomas Chatterton and Henry Kirke White, greatly enhanced her reputation.